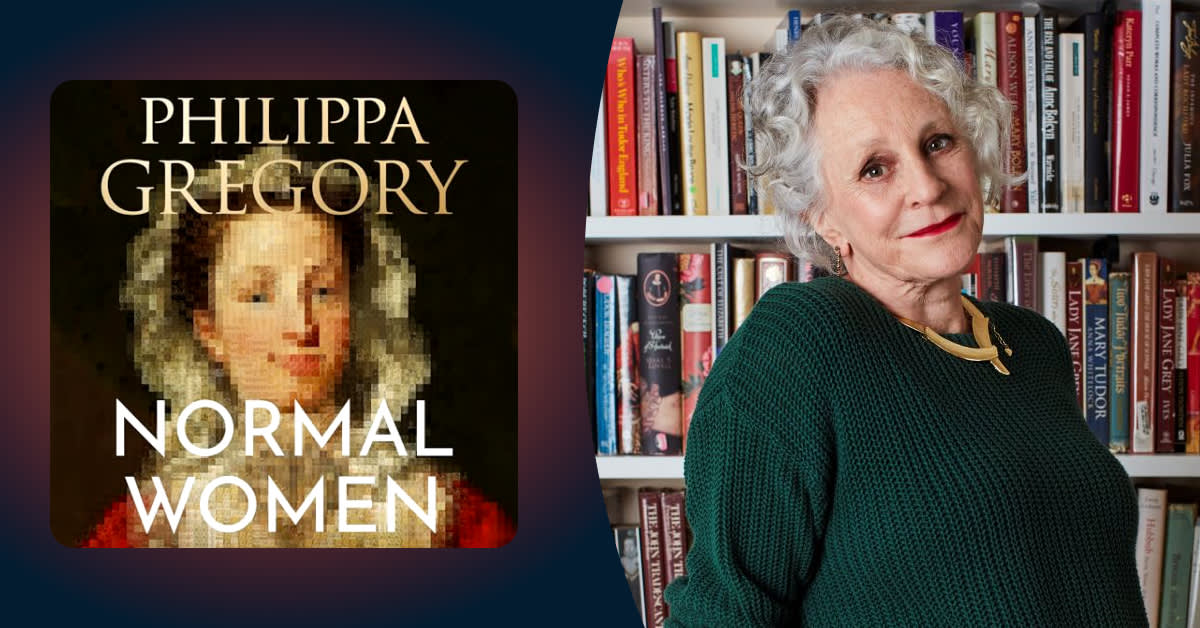

In her latest book Philippa didn’t need to delve into her imagination to tell the stories of women in history, instead she dug into the archives and has captured in Normal Women the everyday lives of women who made it into our newspaper reports and court records but not into the history books. From pirates to pilots, housewives to hermits, Normal Women tells us about the women who wrote, who rode, who cooked, who worshipped and those who went to war.

We asked Philippa to tell us more about what inspired her to turn to non-fiction and how she uncovered the many roles women played in our history.

What inspired you to write Normal Women?

In my fiction, I am almost always writing the history of women who are missing from the record – and I began to ask myself, why is that? Why do we accept a history of England where women are invisible? What we read is a history of men, as viewed by men, and as recorded by men. From the research for my novels, I knew it wasn’t because women were not doing anything, but that the record keepers only made note of women when they did something out of the ordinary: criminal, or even the very beautiful, the saintly or the doomed. Part of my work in writing a history of Normal Women has been recognising the normality of women, however they are named: rioting women, power-mad women, manipulative women, viragoes, angels, witches.

Your novels often centre on women of wealth or aristocracy while Normal Women covers women’s lives throughout society. Why was this important to you?

My first female fictional biography was The Other Boleyn Girl - the story of Mary Boleyn, sister to the more famous Anne Boleyn and researching that I discovered a network of fascinating women at the Tudor court. One led me on to another. But I was soon aware that outside this circle for which we have some historical records – there were other networks of women also struggling for survival, making money, owning land, even commanding armies and ruling people. I didn’t want to highlight one or two, I wanted to look at as many as possible in the context of the society that was usually trying to exclude them - in order to spare men from their powerful frightening competition.

Given that many historical accounts are written by men, often about men, how did you find researching and writing Normal Women?

The many thousands of normal women I researched for this book had left a just a tiny trace – a footnote, a court report, or a line in a will. For the last 10 years, I’ve been following these threads to reassemble the history of women in England. I am indebted to the work that historians of women have already done, from the early 1900s when women were able to study history at university, we see the first great histories of women appear, they are succeeded by biographers of heroines, family histories, social historians and then editors of lists of top ten women. All these publications describe women in different contexts and I drew on them to write a national history of women across nine centuries.

Were there any events or situations that surprised you?

Oh so many! That women had equal pay in 1349 after the Black Death, and lost it again as employers and landlords deliberately forced women’s pay down. That there was a higher rate of rape conviction in Elizabethan England with no police force, or forensic science than we have today. Elizabethan judges convicted about 20% of the rapists brought to court – we convict fewer than 2%. But probably - if I can only pick one - it’s that women’s ‘nature’ has been defined by men for centuries and this ever-changing imaginary label limits expectations on women, and demands that women live up to an impossible standard, or live with a sense of failure or rebellion. Even today – women are expected to be emotional and caring – and so work underpaid in caring professions and for their families for free. This keeps women’s wages down in a far more subtle way than the 14th century laws!

Were there any particular women you learned about that you found inspiring or that you felt you just had to tell people about?

Again, there are so many, it’s really not fair to pick just one. Though I am rather a fan of Agnes Hotot, who was born in 1378 and put on full jousting armour to take the place of her father who had fallen ill before a fight. She unhorsed her father’s enemy in a duel and only then, as he lay on the ground, did she remove her helmet, let down her hair and take off her breastplate to show her breasts – to prove he had been beaten by a woman. Agnes married into the Dudley family and they celebrated her victory with a crest showing a woman wearing a military helmet with loosened hair and her breasts exposed.

Your book covers several hundred years – is there a particular period in time in which you’d have liked to have lived?

I’m often asked this question and I always used to always say, don’t choose a period before 1850 when the Married Women’s Property Acts came in, allowing all married women, as well as estranged wives, to keep their own income or inheritance. Then you’d probably also want to wait for the 1920s for the vote and then the 1960s for reliable contraception to reduce the chances of unwanted pregnancies. But having studied women’s history from 1066 to the present day I would only recommend returning as a wealthy white man.

Finally, which audiobook book would you select as your favourite?

I listen to audio books for mood and not for study – so all my research is done on ebooks or paper books. But I was blown away by Virginia Woolf’s Mrs Dalloway read by Juliet Stevenson. The clarity and the strangeness of Woolf’s writing really suits reading aloud. I find this hard to read on the page but the audiobook makes me take it at the right lyrical evocative pace.

Normal Women by Philippa Gregory is out now.

Discover more listens by Philippa Gregory on her author page and hit ‘Follow’ to stay up to date with new releases.