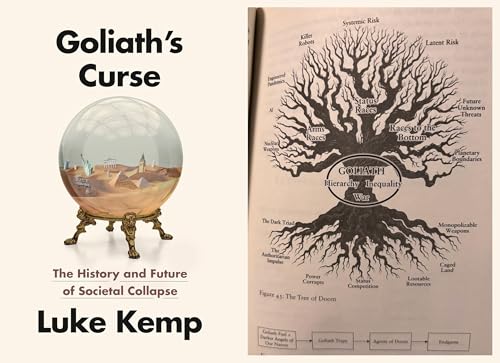

Using the Stone of Democracy to Slay the Goliath of Inequality

Goliath's Curse: The History and Future of Societal Collapse

By: Luke Kemp

Published: 2025

592 Pages

Briefly, what is this book about?

By most accounts, civilization, which is to say the large Hobbesian state, is a good thing. Kemp doesn't necessarily agree. In his account, states are lumbering, tyrannical, extractive Goliaths, cursed to grow bigger, more oppressive and more brittle until they are eventually brought down by a "stone" that hits in just the right place.

Civilization forms out of dominance hierarchies, and these hierarchies generally only move in one direction, towards greater inequality, greater extraction, and more self-interested decisions. This leads to ever increasing fragility and eventual collapse. Collapse might actually be a better place for the masses of people, though it's often quite bloody to get there.

Though if that's how it played out in the past, Kemp doesn't think it will necessarily play out that way going forward. If (when?) civilization collapses this time, it will be far more apocalyptic.

What authorial biases should I be aware of?

Kemp is associated with the Centre for the Study of Existential Risk at Cambridge. I was recommended this book by the sagacious Florian U. Jehn of the excellent Existential Crunch blog. Jehn knows his stuff which gives me the confidence to safely locate Kemp as an important scholar in the genre of collapse research, with an interesting, albeit populist/anti-elite take on the subject.

Who should read this book?

Kemp draws heavily on the ideas of James C. Scott (Seeing Like a State and Against the Grain) and writes in opposition to the ideas of Steven Pinker (in particular The Better Angels of Our Nature). If you find yourself similarly situated, you'll enjoy this book.

It's also a great book for anyone who can't get enough discussion of existential risk. And really given the stakes we should be considering as many viewpoints as possible.

What does the book have to say about the future?

As you might imagine, Kemp's vision of the future is pretty bleak. He is not a techno-optimist, rather he sees in technology the emergence of a new Goliath, a new arena of dominance and extraction. He has a certain amount of hope, but it all revolves around using democracy to disrupt the ratcheting up of inequality and elite power, which seems like a tall order.

Specific thoughts: Past, present, and future collapse

Jan 30 202620 mins

Jan 30 202620 mins Jan 28 202610 mins

Jan 28 202610 mins Jan 17 202612 mins

Jan 17 202612 mins 10 mins

10 mins 7 mins

7 mins 11 mins

11 mins 8 mins

8 mins 13 mins

13 mins