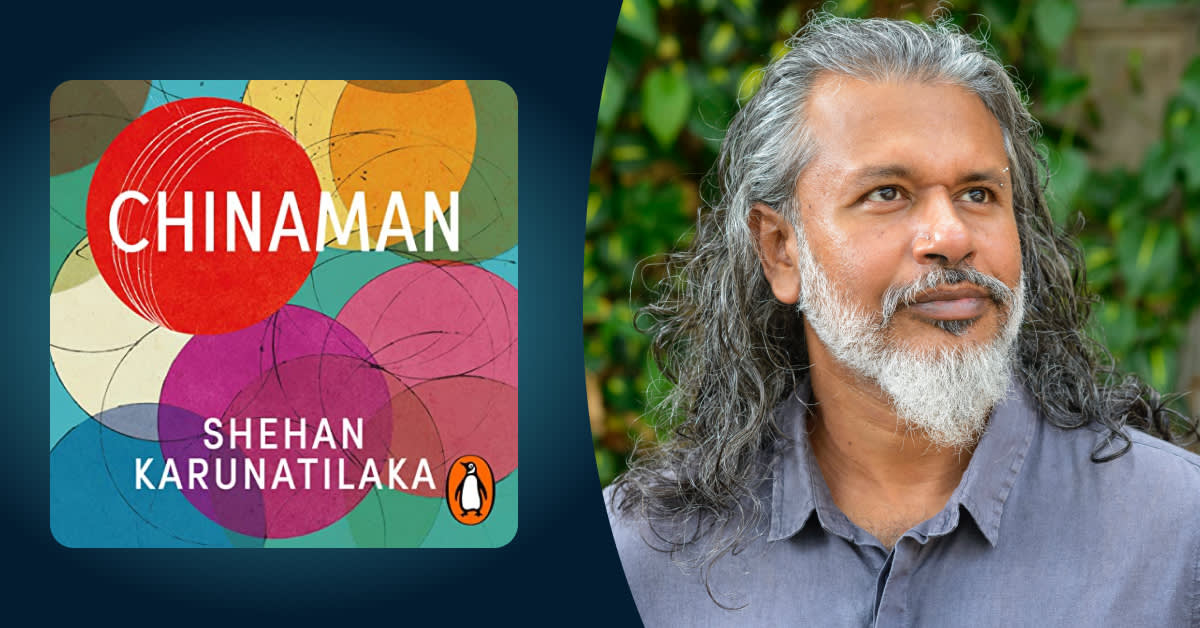

Your debut novel centres around cricket. How important is cricket to the Sri Lankan population? How do you think it influences the culture?

Before it changed its name to Sri Lanka in the 70s, Ceylon was known for its tea, its elephants and its beaches. By the late 20th century, it had become infamous globally for two things: a civil war that invented the suicide bomb, and a Cricket World Cup in 1996 that no one expected them to win.

Despite being a war-torn, underachieving nation, we proved we could be world-class at one thing even if it was just cricket. This fairy tale underdog story fooled us into believing we could triumph at anything with our talent and flair, and ignored the need for infrastructure, funding or much of a plan.

We enjoyed a golden age of Sri Lankan cricket for the next few decades, and even though the team is struggling now, there’s always that blind optimism that Sri Lanka can turn on the magic like we did in 1996.

I think many of us carry this misplaced confidence when we look at our country and its failings. Despite last year’s economic collapse and leadership debacles, many Sri Lankans still believe that we can smash a few sixers in the final over and whack the cup.

How did Chinaman come about?

I was in my 20s during the 1996 world cup and while I was swept up in the fairy tale, I also saw the absurdity of a divided nation coming together just for a cricket tournament. A Sinhalese majority rallying behind our lone Tamil player, Muralitharan. The government and the rebels ceasing hostilities till the cup was won.

I also happened to be a failed left-arm Chinaman bowler, and fantasized as sad aging men often do, about being a world-class cricketer and saving the day. I also remember how a generation of amateur Sri Lanka cricketers had their careers stifled by the war and a lack of resources.

The idea that the greatest cricketer of all time went unnoticed by the rest of world because he was unfortunate enough to play for SL during the 80s, was a delicious one. So, inspired by Peter Jackson’s Forgotten Silver, Nick Hornby ’s Fever Pitch, Woody Allen’s Zelig and a hundred pointless cricket matches, I began typing a rare Lankan story that didn’t involve the civil war.

How important is it to you to bring Sri Lanka’s history to audiences around the world?

That’s not really my job or agenda. Like most, I’m a fan of a well-told story. While I do enjoy literary fiction and sometimes get accused of writing it, I also love genre fiction and admire the skill of a well-crafted mystery, thriller, horror or detective story. Chinaman is, at its heart, a missing persons detective story, just as Seven Moons is a murder mystery, albeit one where the corpse is the detective.

I just happen to be blessed or cursed with the canvas of Sri Lanka’s turbulent history to set my stories in. The island paradise is full of bizarre conspiracies, untold sagas and astonishing tales. I draw from these, which I guess add an unusual dimension for readers unacquainted with the subcontinent.

But that’s just a by-product. The main aim is to tell a compelling story set in an intriguing place. If readers are interested in Sri Lankan history, there are far better books than mine to get lost in. I’m happy if the books lead to a curiosity about Sri Lanka. But that’s not the main aim.

How do you ensure listeners or readers are bought into the story?

Whether it’s music or painting or literature, the voice of a piece is everything. I don’t believe I have a book until I find the voice of it. The story of Pradeep Mathew, the forgotten cricket genius, only came alive because I had drunk sportswriter WG Karunasena to tell it. The voice of a bitter, wise, funny and tragic old uncle, rambling after a few too many drinks was a thrill to write. And it’s a joy to listen to, thanks to the dramatic artistry of Shivantha Wijesinghe, whose voice narrates both my books.

How do you create compelling characters? Are any characters based on people you know?

They may start off as based on real people, but they eventually evolve on the page in unexpected ways. With Chinaman, I based some characters on real cricketers, as I did the ghosts of Seven Moons on real unsolved murder victims. After numerous drafts the characters speak in their own voice and behave contrary to the plot and that’s when they start telling me where they want to go. This happens around the 3rd or 4th draft, and is both magical and terrifying.

Were there any learnings from Chinaman that influenced your writing process or ideas for The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida.

Just the basics of finding the time and space to write every day. Which is most of the challenge. Then the matter of researching widely and making more notes than you need. Then being patient enough to rewrite it as many times as it needs. But the main thing is to not talk about the thing until you’ve written it.

How was the experience of winning the Booker Prize in 2022?

Terrifying, astonishing and pretty sweet. It’s opened many doors, brought me new readers, and made me more friends than I probably need. In theory it should mean I can focus on my next book and write fiction fulltime. In practice it means I have no time to write with all the travelling, speaking, interviewing, meeting, answering mail and doing admin. But grumble I cannot. It’s a marvellous honour and I’m enjoying the circus though I do hope it’ll all be over soon. Just so I can go back to my dull life of reading strange stories and trying to write them.

Which authors inspired you growing up? How do you hope to inspire new generations of writers?

My first grown-up books were by Agatha Christie, Stephen King, , Douglas Adams and PG Wodehouse. I think you might see all their influences in my writing. Then of course the great South Asian wave of wonderful writers like Rushdie, Seth, Ghosh, Tharoor, Roy, Ondaatje, Gunesekera and Selvadurai, gave me and my MTV generation permission to tell stories in our own voices.

I’m only on my third book, so I’ve got a long way to go before I can think of imparting inspiration to future generations. I’ll be happy if the books are still in print in a generation’s time. And if there are still humans around to read them.