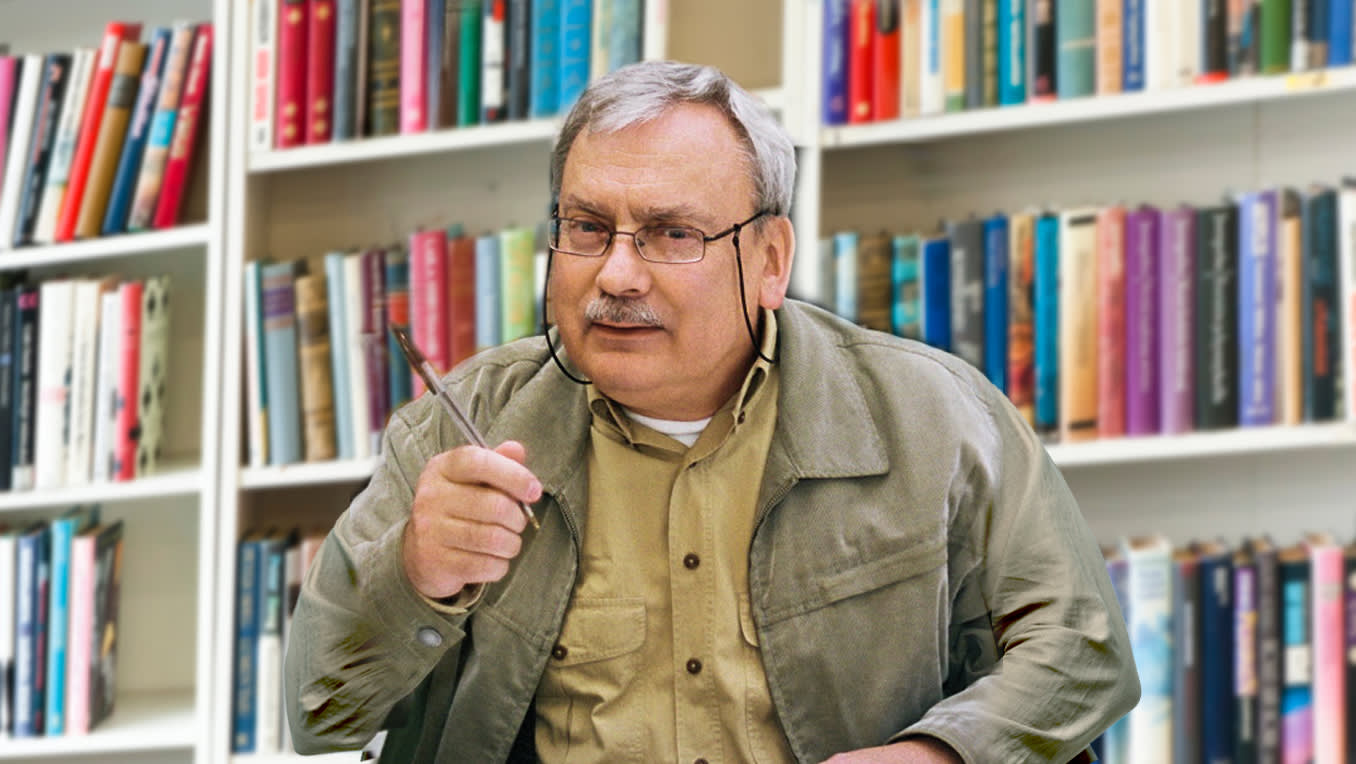

Polish author Andrzej Sapkowski’s fantasy series, The Witcher Saga, has become a global phenomenon. What began as a series of short stories about a mutant monster hunter named Geralt is now a massively popular Netflix show, multiple video games, and a best-selling audiobook series narrated by acclaimed performer Peter Kenny. Sapkowski recently gave a rare interview for Audible, and as fans might expect, his answers were as intriguing and cryptic as the saga itself.

Interview with Andrzej Sapkowski

Note: This interview has been translated and edited from the original German.

Christian Handel: As the author of The Witcher Saga, what do you like most about Geralt?

Andrzej Sapkowski: Geralt is a fictional character, created to serve the story, which revolves around him. If the fictional character serves the story well, an author likes his character. If an author doesn't like his character, finds him unlikeable or faulty in any part or aspect, it means an author has done his job poorly. Or he is schizophrenic. Or both.

CH: Blood of Elves came out in 1994. There are a lot of novels which people love but are forgotten over time. Some maintain their significance over time. Why do you think The Witcher Saga has remained so popular?

AS: Well, very true is the proverb: habent sua fata libelli, or “books have their own destinies.” The rest is silence.

CH: Which part of your fantasy world do you like most, and why?

AS: My fantasy world was created to serve the story. So look above, the answer to question number one.

CH: How much did you know about that world and its characters when you first started to write about them? And how long did it take you to create such an epic setting?

AS: Nothing at all. Don't forget I began with short stories; you don't create universes in short stories, there is—literally and metaphorically—no place for them. Later, when my stories started evolving into full novels, the necessity of some coherent background became imminent. And slowly, step by step, something resembling a universe started to emerge. But it’s only in the background, so it plays a secondary role in the story.

CH: Your short stories seem to draw heavily from folklore and fairy tales. Why did you decide to play with these motifs in your writing?

AS: One of the subgenres of the fantasy genre—there are several of them—is called the retelling, which consists of taking classic fairy tales, fables, legends, or myths and telling them anew, whether changed, modified, or sometimes even distorted or twisted in perverse ways. I simply used the classic technique.

"Neither hardness nor difficulty scares us. We are fearless."

CH: What’s your favorite monster in Slavic mythology?

AS: When I was a kid, the scariest was Baba Yaga, the child-eating witch. And the most likeable ones were rusalkas, water-dwelling nymphs who take the shape of women. Now I’m not a child anymore, and I do not favor anyone. Or anything.

CH: The Witcher Saga started with short stories. In your opinion, what are the advantages of short stories?

AS: Isaac Asimov used to say that a short story is a straight line; a novel is a plane. In the story, the writer—and the reader—go straight from point A to point B. In the novel, you move in many directions. Both have their advantages, and disadvantages, depending on what an author (or reader) likes or dislikes.

CH: What made you decide to expand The Witcher Saga into a series of full-lengths novels? Did you come up with a story that demanded an epic scale? Or did you want to spend more time with the characters and therefore created a huge story arc for them?

AS: Once again, Isaac Asimov: straight line and plane. For me it was a natural consequence. At some point, I felt tied up and limited by the size of a short story or a novella, and desired to abandon the line—and ride the wide plane.

CH: Your novels are beloved all over the world. Which novels did you love as a child? As an adult?

AS: I was an avid reader as a kid, and a lucky one in addition, as there were innumerable books in my home since my parents were avid readers, too. And they encouraged me to read. Books were always an important part of my life, it was ever and it remains so. These days, I read something like forty books a year.

CH: What compels you to write?

AS: I’m not sure. I’d bet on the muse. She’s most likely the guilty party.

CH: Do you still plan to write another prequel novel similar to Season of Storms? Can you give us some hints on what you’ll be writing next?

AS: I never disclose my plans, sorry. Be patient.

CH: Does it get harder or easier to write stories set in The Witcher’s amazing world?

AS: Neither hardness nor difficulty scares us. We are fearless.

CH: In what ways has the fantasy genre changed in the last 25 years?

AS: The genre has become more and more popular, winning more and more readers. Greater demand requires greater supply, so there are more and more writers in the field, too—very different writers. So the genre becomes more manifold and diverse as a result.

CH: If you could invite two fictional or historical characters for a dinner party, whom would you choose and why?

AS: Ernest Hemingway and Umberto Eco. I consider them the best writers of all time.

CH: Did you watch The Witcher on Netflix?

AS: Of course. And long before the rest of the world did. I was given special access and a unique password.

CH: A lot of readers and listeners would argue that movie and TV adaptations of books and audiobooks often fall short compared to their inspirations. How hard was it for you to watch the TV show and judge it on its own merit?

AS: “Judge not lest ye be judged.” Matthew 7:1-3.

CH: Not everything that’s in an epic saga can make it into a TV show. Is there anything you do miss especially?

AS: Yes, there is.

CH: On the other hand, are there advantages for the audience to experience your epic saga as a TV show, comic book, or video game?

AS: Yes, there are.

CH: What about audiobooks?

AS: The same.

Photo Credit: Wojciech Koramowicz